The payment stablecoin (PS) legislative endgame is near. There is a clear imperative from the White House to prioritize stablecoin legislation and preserve the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Both chambers of Congress are forming a working group to deliver a clear regulatory framework for digital assets. Bipartisan agreement appears within reach.

On February 6, House Financial Services Committee Chairman French Hill (R-AR) and Digital Assets, Financial Technology, and Artificial Intelligence Subcommittee Chairman Bryan Steil (R-WI) released a discussion draft of the “Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy Act of 2025” (STABLE Act of 2025). Just two days prior, on February 4, a bipartisan group of U.S. Senators led by Senator Bill Hagerty (R-TN) introduced the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins (GENIUS Act). Co-sponsors of the GENIUS Act include Chairman of the Senate Banking Committee Tim Scott (R-S.C.), Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.).

Each proposal aims to establish a clear regulatory framework for PS and is the long-standing product of multiple stakeholder engagement, including the U.S. Treasury, Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), state regulators, and various crypto industry participants. The interaction between these participants has resulted in two proposals that are largely aligned, and that more carefully balance the role of the federal banking agencies and state regulators in overseeing and regulating PS issuers.

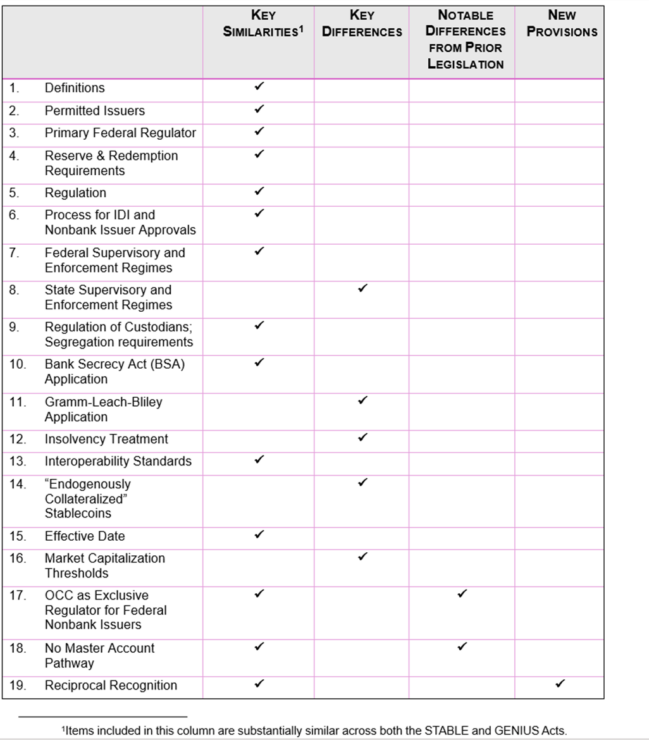

Despite their substantial similarities, there are several key differences and new features worth exploring. In many cases, these differences appear to be minor or technical in nature, except where noted in section (ii) below. There are also some notable differences across the proposals compared to prior legislation — namely, defining the OCC as the exclusive federal regulator for nonbank PS issuers regulated at the federal level, and omitting any reference to a master account pathway for nonbank PS issuers.

The analysis below tracks these points along with an important new provision on reciprocal recognition, previewing the U.S.’s role in seeking to harmonize PS requirements across the global regulatory framework. First, a chart illustrating the substantial alignment between both proposals:

(i) Key Areas of Substantive Agreement Across Proposals

Key Definitions. Both proposals define “distributed ledger” identically (referring only to “public” distributed ledgers); PS are not a “security” under the federal securities laws. There are slight differences, however, in how each proposal defines “payment stablecoin.”

The GENIUS Act’s use of “and” in its definition[1] indicates that a PS must not only be designed to be used as a means of payment or settlement, but it also must: (i) be obligated to convert, redeem, or repurchase it for a fixed monetary value; and (ii) represent that it will maintain a stable value relative to this fixed amount. By contrast, the STABLE Act’s use of “or” in its definition[2] suggests more flexibility — i.e., a PS must be one that is or is designed to be used as a means of payment or settlement, but the PS issuer could either: (i) be obligated to convert, redeem, or repurchase it for a fixed monetary value; or (ii) represent that it will maintain a stable value relative to this fixed amount.

- Note: It is not clear whether these technical differences are intended.

Permitted PS Issuers. Issuers are either:(i) approved subsidiaries of insured depository institutions and credit unions (together, IDIs); Federal qualified nonbanks (Federal Nonbank Issuers); or state qualified and licensed PS issuers (State Issuers).

- Note: The STABLE Act definition of a Federal qualified nonbank PS issuer includes a subsidiary of a nonbank entity; the GENIUS Act definition does not refer to a subsidiary entity in its definition of a “Federal Qualified Nonbank Payment Stablecoin Issuer.”

- It is unlawful for any person other than a permitted PS issuer to issue a PS in the U.S. Therefore, to the extent any payment stablecoin issuer operating today does not meet the various reserve and redemption requirements described below — e.g., does not provide monthly attestations detailing reserves — unless such issuer complies with these requirements, they will not be permitted to continue issuing PS in the U.S. Failure to be an approved PS issuer could result in civil penalties of up to $100,000 per day.

Primary PS Federal Regulator. The primary federal regulator for any one IDI is their existing primary federal regulator (Federal Reserve, OCC, FDIC, or NCUA). The Primary PS Federal Regulator for a Federal Nonbank Issuer is the OCC.

Reserve and Redemption Requirements. Issuers are required to maintain reserves backing their PS on at least a one-to-one basis. Reserves include U.S. coins and currency, demand deposits held at IDIs (and regulated foreign banks), short-term Treasury bills, central bank reserves, and other specified assets (generally consistent with current criteria for high-quality liquid assets)).[3] Issuers are also required to publicly disclose their redemption policy, establish a timely redemption process, and describe their reserve composition and outstanding issuance monthly. Generally, reserves may not be pledged, rehypothecated, or reused, except to create liquidity and meet reasonable redemption requests, and so long as such reserves are, among other conditions, in the form of short-term US treasuries with a maturity of 90 days or less.

- Note: Only the GENIUS Act anticipates demand deposits being held at regulated foreign banks (in addition to U.S. IDIs). There is also a broader basket of reserves contemplated in the GENIUS Act, including notes and bonds with specified maturities; reverse repurchase agreements with a maturity of seven days or less that are collateralized by U.S. Treasury bills with a maturity of 90 days; reverse repurchase agreements, subject to specific terms; and certain money market funds. The GENIUS Act includes short-term Treasury bills with remaining maturity of 93 days or less (compared with the STABLE Act’s reference to maturity of 90 days or less).

Regulation. The Primary PS Federal Regulators have broad authority to jointly issue capital, liquidity, and risk management requirements tailored to a PS issuer’s capital structure, riskiness, complexity, financial activities, size, and “any other [appropriate] risk-related factors . . .” The OCC can consult with other Primary PS Federal Regulators regarding regulation of Federal Nonbank Issuers. State Issuers can be regulated at the state level so long as the state level regulation meets the standards and requirements applicable to IDIs and Federal Nonbank Issuers. Rules must be issued no later than the end of the 180-day period following enactment.

- Note: Under the GENIUS Act, a State PS regulator “shall” (not “may” under the STABLE Act) issue capital, liquidity, and risk management requirements. The GENIUS Act incorporates additional enumerated liquidity and risk management requirements — i.e., interest rate risk management standards, appropriate operational, compliance, and IT risk management standards, including BSA and sanctions compliance tailored to the business model and risk profile of the PS issuer. Only the GENIUS Act carves out the applicability of leverage capital requirements. Also, as discussed below, only the GENIUS Act has a PS issuer market capitalization threshold that would govern under what circumstances an issuer could remain regulated at the state level.

Process for IDI and Federal Nonbank Issuer Approvals. An IDIs Primary PS Federal Regulator receives and reviews applications from an IDI that seeks to issue PS through a subsidiary. Similarly, the OCC would receive and review applications from any nonbank entity that seeks to issue PS through a subsidiary. Determination on the application would be made based on the ability of the applicant, and its financial condition and resources to meet various requirements (e.g., reserve and redemption requirements; additional capital, liquidity, and risk management rules yet to be implemented). Assuming an application is complete, there is a 120-day period within which a Primary PS Federal Regulator must render its decision. Any applications that are denied shall explain the denial with specificity.

- Note: The STABLE Act includes a 45-day window for determining application completeness. The GENIUS Act does not provide a specific window for such a determination.

Federal Supervisory and Enforcement Regimes. IDIs are subject to supervision by their existing primary federal regulator. Federal Nonbank Issuers are required to submit, on request, reports to the OCC regarding financial condition, systems for monitoring and controlling financial and operating risks, and compliance. The OCC can examine Federal Nonbank Issuers on various risks, including systems monitoring, and to determine any threats to safety and soundness or financially stability. The OCC maintains the ability to suspend or revoke a Federal Nonbank Issuer’s registration if it (or an institution-affiliated party (IAP))[4] is materially violating or has materially violated the Act or any implementing regulation.

State regulators can issue orders and rules to the same extent as the primary federal PS regulators consistent with those applicable to IDIs and Federal Nonbank Issuers. In “exigent circumstances,” the Federal Reserve can, upon at least five days prior written notice to the state regulator, take an enforcement action against only a State Issuer that is an IDI (or an IAP) for compliance violations. Similarly, in “exigent circumstances,” the OCC can, upon at least five days prior written notice to the state regulator, take an enforcement action against a Federal Nonbank Issuer (or IAP). These “exigent circumstances” are to be defined in separate Federal Reserve and OCC rules no later than the 180-day period starting after enactment.

- Note:

- Both proposals omit any role for the FDIC (or the NCUA) in taking an enforcement action under “exigent circumstances,” even where the FDIC would be the primary federal regulator of the state nonmember IDI. Regardless of whether additional federal regulators play a role beyond the OCC and Federal Reserve in this context, Congress should consider a similar joint rulemaking mechanism (as would apply to capital, liquidity, and risk management rules) so that exigency-related definitions and enforcement processes are uniform and transparent for Federal Nonbank Issuers and IDIs.

- Only the STABLE Act contains a provision stating that the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act’s (GLBA) application to State Issuers (and presumably also the “exigent circumstances” provisions) does not preempt “any law of a State and do[es] not supersede any State licensing requirement.” The GENIUS Act’s approach here is confusing and unclear, relying on the application of “Host State” and “Home State” law, which are both undefined terms. Congress should consider aligning these provisions so that the GLBA’s application is clear in all circumstances, and for all permitted PS issuers.

Regulation of Custodians; segregation requirements. Custodial and safekeeping services can only be provided by entities that are either regulated and supervised at the Federal level or supervised at the state level, and that comply with segregation requirements (as defined in the proposals or by the SEC or CFTC). Segregation requirements generally involve: (i) treating the PS, private keys, cash, and other property held on behalf of the customer as belonging to such customer; and (ii) taking appropriate steps to protect customer property from the claims of a custodian’s creditors.

Customer property and custodian property shall not be commingled, except: (i) customer property may, for convenience, be commingled and deposited in an omnibus account holding the PS, cash, and other property of more than one customer at an IDI or trust company; and (ii) lawful custody-related service fees may be withdrawn from the omnibus account. Entities that seek to provide custodial and safekeeping services are required to submit to the applicable primary regulator information concerning their business operations and processes, in a manner to be determined by the primary regulator.

Bank Secrecy Act Application. Permitted stablecoin issuers are financial institutions under the BSA.

Interoperability Standards. The Primary Federal PS Regulators, in consultation with National Institute of Standards and Technology, other standard setters, and state governments, shall prescribe standards for PS issuers to promote compatibility and interoperability.

- Note: The “other standard setters” language in this provision — which has been a feature of various legislative proposals — overlaps with the proposals’ new “reciprocal recognition” provision discussed below. This new provision generally addresses the Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury’s role in creating and implementing reciprocal arrangements with other jurisdictions to facilitate interoperability.

Effective Date. Each Act would take effect the earlier of 18 months after enactment or the date that is 120 days after the date on which the Primary Federal PS Regulators issue any final implementing regulations.

(ii) Key Differences Across Proposals

Market Capitalization Thresholds. The most significant difference between the proposals is the GENIUS Act’s insertion of a hard threshold for determining federal or state oversight. Under the GENIUS Act, an issuer could be regulated at the state level if: (i) its total market capitalization does not exceed $10 billion; and (ii) the relevant state regulatory regime is “substantially similar” to the Federal regulatory framework.[5]

In order to meet the “substantially similar” test, state regulators would be required to submit to the Secretary of the Treasury an initial certification, which remains subject to an annual recertification process. The U.S. Treasury determines whether a state’s regulatory regime is substantially similar to the federal regulatory framework, although this determination remains subject to appeal to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. If a state framework is deemed not substantially similar, the issuer will be subject to the federal regulatory framework, regardless of its market capitalization. If an issuer exceeds the $10 billion threshold, it must transition to the federal regulatory framework within 360 days of exceeding the threshold. There is also an undefined waiver process for issuers who exceed this threshold, but request to remain state regulated.

By contrast the STABLE Act contains no such threshold or “substantially similar” test, presumably leaving the choice of whether to be regulated at the state or federal level up to the issuer, regardless of the issuer’s market capitalization. Apart from whether hardwiring a threshold for federal oversight is a good idea, the idea of having “substantially similar” strongly homogenous federal and state regulatory regime is an important one as it promotes regulatory clarity and consistency and minimizes opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.

- Note: Although addressed in both proposals, to the extent a State Issuer were able to successfully obtain a Federal Reserve master account, such issuer would be subject to some form of federal oversight.

State Supervisory Enforcement Regimes. State regulators would continue having the supervisory, examination, and enforcement authority over State Issuers. They could opt, however, to enter into memoranda of understanding with the Federal Reserve (and OCC), under which the Federal Reserve (and OCC) would carry out their supervision, examination, and enforcement authority. Under these mutually agreed memoranda of understanding, state regulators and the Federal Reserve (and OCC) would share information on an ongoing basis.

- Note: The STABLE Act envisions both the Federal Reserve and OCC entering into memoranda of understanding, whereas the GENIUS Act only envisions the Federal Reserve doing so. It is not clear whether the GENIUS Act’s omission of the OCC in this context is an oversight — presumably the OCC would have an interest in entering into a memoranda of understanding regarding nonbank issuers regulated at the state level. Separately, it is not clear under what circumstances a state regulator would opt into entering a memoranda of understanding with one or multiple federal banking agencies, especially since exercising this option would usurp such state regulator’s ability to supervise, examine, and enforce all State Issuers in that state.

Application of Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. Each IDI, (Federal Nonbank Issuer), and State Issuer is deemed a “financial institution” under title V of the GLBA.

- Note: The STABLE Act includes Federal Nonbank Issuers within the category of Permitted PS Issuers subject to title V of the GLBA, but the GENIUS Act does not. It is not clear whether this difference is a drafting oversight or a reflection of the position different stablecoin issuers have taken regarding GLBA’s applicability. To the extent issuers have not already done so, they should strongly consider planning for GLBA compliance, which at a minimum will include implementing a compliance management system to prepare and deliver privacy notices under the GLBA Privacy Rule as well as ensuring information security programs are aligned with the GLBA Safeguards Rule.

Insolvency Treatment. The GENIUS Act contains a stand-alone insolvency section. It states that in any insolvency proceeding of a PS issuer, claims of PS holders will have priority over other claims against the issuer. It further clarifies that a PS issuer (other than an IDI) can be a “debtor” as that term is defined under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. While the STABLE Act does not contain its own stand-alone insolvency section, or any of these provisions, it requires that an issuer take “appropriate steps” to protect customer property from the claims of a custodian’s creditors.

- Note: While it may be helpful to clarify that a PS issuer can file for bankruptcy, the GENIUS Act’s approach appears to assume that reserves backing a PS would be property of the issuer’s bankruptcy estate, subject to priority. The segregation requirements in both proposals, however, appropriately require that reserves be segregated from the issuer’s proprietary assets, and held or custodied at IDIs, for the benefit of PS holders. An alternative path forward on this issue would be to clarify that in any insolvency of a PS issuer, the reserves backing the PS are not property of the issuer’s bankruptcy estate, and therefore not subject to the ordinary (and elongated) bankruptcy claims process.

Endogenously Collateralized Stablecoins (ECS). Under both proposals, the US Treasury will lead a study of ECS (commonly known as algorithmic stablecoins) and analyze, e.g., benefits and risks, participants, utilization, nature of reserves, types of algorithms employed, governance, advertising, and clarity and availability of consumer disclosures. The STABLE Act goes further, calling for a moratorium on ECS during the two-year period after enactment of STABLE Act. The GENIUS Act does not include an ECS moratorium.

(iii) Notable Differences from Prior Stablecoin Legislation

OCC as Exclusive Primary PS Federal Regulator for Federal Nonbank Issuers. Both proposals grant the OCC the exclusive authority to approve, supervise, and regulate Federal Nonbank Issuers. Prior proposals, like the Clarity for Payment Stablecoin Act of 2023, envisioned that the Federal Reserve would play a role in supervising Federal Nonbank Issuers.

No Mention of Master Account Pathway. Prior draft bills, like the Stablecoin Trust Act of 2022 released by former Senator Toomey (R-PA) envisioned that certain PS issuers would be eligible for Fed master account access and services. It included a clear “on ramp” for master account access and was designed to settle the question about whether the Federal Reserve would broaden eligibility for master account access to stablecoin issuers, who today remain outside the federal bank regulatory perimeter. It also envisioned not only a deposit account for state-regulated stablecoin issuers, but also various services including settlement, securities safekeeping, and Federal Reserve float.

Notably, the Stablecoin Trust Act of 2022 preceded the Federal Reserve’s final guidance on “Tier 3” master account eligibility, which include state-chartered depository institutions that are not subject to prudential supervision by a federal banking agency. It also preceded several court decisions where courts upheld the Federal Reserve Banks’ discretion to deny master account requests, reinforcing the principle that access to master accounts is not an entitlement but a privilege subject to regulatory scrutiny.

More recent bills like the Clarity for Payment Stablecoin Act of 2023 made no mention of whether nonbank issuers would be granted access to a Federal Reserve master account (or the discount window). As a general matter, state-chartered depository institutions have found it challenging to obtain master accounts under the Tier 3 regime. To the extent the Federal Reserve needs Congressional authority to make PS issuers eligible for a master account, this should be clarified in a final proposal. Currently, if either proposal is enacted in current form, there would still be no master account pathway for stablecoin issuers. While this may leave some nonbank stablecoin issuers disappointed, it is also possible the Federal Reserve may revisit master account guidelines following enacted stablecoin legislation, either independently of or in conjunction with efforts to create a federal payments charter.

(iv) New Provisions

Reciprocal Recognition. Both proposals include a new provision stating that the Federal Reserve, in collaboration with the U.S. Treasury, “shall create and implement reciprocal arrangements or other bilateral agreements between the U.S. and jurisdictions with substantially similar PS regulatory regimes to facilitate international transactions and interoperability with US dollar-denominated stablecoins issued overseas.”

On its face, this new provision appears designed to foster bilateral cooperation and preempt any frictions across “substantially similar” jurisdictions’ stablecoin laws. If either proposal is enacted, the U.S. would be one of the last major jurisdictions to enact stablecoin legislation, meaning it will need to look to other “substantially similar” PS regulatory regimes to guard against cross-border regulatory fragmentation. If the U.S. and substantially similar jurisdictions are not keenly focused on understanding the interaction between their legal frameworks — including whether and to what extent reserves must be held in their respective jurisdictions’ banks — we risk creating an uneven playing field for issuers, potentially resulting in higher costs, unworkable business models, less competition, and greater instability across the financial system. These concerns are real,[6] and Congress is wise to incorporate reciprocal arrangements and bilateral agreements as a means of facilitating cross-border transactions and promoting global competition.

Conclusion

While enacting stablecoin legislation in the U.S. would mark a pivotal moment in both the domestic and global regulation of digital assets, the proposals’ reciprocal recognition provisions make plain that enactment of U.S. regulation is just one part of a multi-jurisdictional legal framework. Harmonizing the application of these frameworks is critical.

Thinking several moves ahead: (i) there remain some unanswered questions regarding a master account pathway (and possible federal payments charter) for PS issuers; and (ii) implementing liquidity, capital, and risk management rules have yet to be proposed. Each of these open items will play a significant role in ensuring permitted PS issuers can effectively compete.

For now, much work has gone into improving a federal and state PS oversight model. This has resulted in two substantially similar proposals, suggesting a reasonable likelihood of near-term alignment on a final bill. As Congress seeks to reconcile proposals, it is critical to ensure that the dual banking-like framework promotes regulatory clarity and consistency and minimizes opportunities for regulatory arbitrage across federal and state frameworks. Any final bill should ensure there is strong homogeneity across federal and state regulation and ongoing engagement between regulators.

[1] See Section 2(14) (“The term ‘payment stablecoin (A) means a digital asset — (i) that is or is designed to be used as a means of payment or settlement; and (ii) the issuer of which — (I) is obligated to convert, redeem, or repurchase for a fixed amount of monetary value; and (II) represents will maintain or creates the reasonable expectation that it will maintain a stable value relative to the value of a fixed amount of monetary value; and (B) that is not — (i) a national currency; or (ii) a security issued by an investment company registered under section 8(a) of the Investment Company Act of 1940 (15 U.S.C. 80a–8(a))”) (emphasis added).

[2] See Section 2(13) (“The term ‘payment stablecoin’ means a digital asset — (A) that is or is designed to be used as a means of payment or settlement; (B) the issuer of which — (i) is obligated to convert, redeem, or repurchase for a fixed amount of monetary value; or (ii) represents will maintain or creates the reasonable expectation that it will maintain a stable value relative to the value of a fixed amount of monetary value; (C) that is not — (i) a national currency; or (ii) a security issued by an investment company registered under section 8(a) of the Investment Company Act of 1940 (15 U.S.C. 80a–8(a))”). (emphasis added).

[3] See 12 CFR 329.20 – High-quality liquid asset criteria.

[4] Under both proposals, an “institution-affiliated party” means any director, officer, employee, or person in control of, or agent for, the permitted PS issuer.

[5] With two exceptions, most PS issuers today fall under the $10 billion threshold.

[6] MiCA’s Stablecoin Gamble: How Europe’s Bank Mandate Could Backfire.