“The theme of this record is love,” wrote Horace Silver in the liner notes to 1968’s Serenade To A Soul Sister, an album whose message chimed with the vibe of the late 60s hippy movement. One of the architects of a popular jazz style known as hard bop, which he developed in the mid-1950s, Silver adopted a more commercially successful soul jazz approach in the 1960s, epitomized by his iconic album, Song For My Father, which rose to No. 95 on The Billboard 200 in 1965, an unprecedented feat for a jazz record. Its follow-up, Cape Verdean Blues, also grazed the pop charts, underlining Silver’s commercial value to Blue Note. Jazz had lost much ground to pop and rock as the 60s progressed, but Silver showed that the genre could still be a force in the modern marketplace. Three years on from Song For My Father’s success, Silver recorded his sixteenth Blue Note album, Serenade To A Soul Sister, a work that is widely considered his final masterpiece.

Serenade To A Soul Sister was recorded across two separate sessions. Typically, Silver recorded exclusively with his working band. For the first session, however, he came to the studio in early 1968 with only one member from his then group: trumpeter Charles Tolliver. Rounding things out were noted tenor saxophonist Stanley Turrentine, whom he described as “a giant on his instrument,” together with bassist Bob Cranshaw and drummer Mickey Roker, stalwarts of many Blue Note sessions.

The all-star quintet session yielded three tunes, beginning with the urgent “Psychedelic Sally” dominated by fanfare-like horns. The track was also notable for Cranshaw preferring an electric bass over an acoustic one. The album’s title track, an elegant soul-jazz waltz, was dedicated to Silver’s mother, whom he described as “the greatest soul sister.” In sharp contrast, “Rain Dance” was a modal swinger that began with Native American-inspired rhythms. “[It] is my interpretation of some American Indians doing a tribal dance around the campfire praying for rain,” Silver explained.

The album’s remaining tunes were cut at a second recording session a month later, in March 1968. This time, Silver used his road band: Tolliver with tenor saxophonist Bennie Maupin, bassist John Williams, and a rising Panama-born drummer called Billy Cobham, fresh out of the army. “A budding young talent to be watched,” was how Silver referred to the sticks man. (In a few years, Cobham would co-found the jazz-rock behemoth Mahavishnu Orchestra and then enjoy a remarkable solo career.)

The hypnotic “Jungle Juice,” lit up by a robust Maupin solo, finds Silver exploring modal jazz territory. “Kindred Spirits,” dedicated to Silver’s three brothers, is more meditative. The horns drop out on the dreamy finale, a slow ballad called “The Next Time I Fall In Love,” with Silver playing in a piano trio configuration.

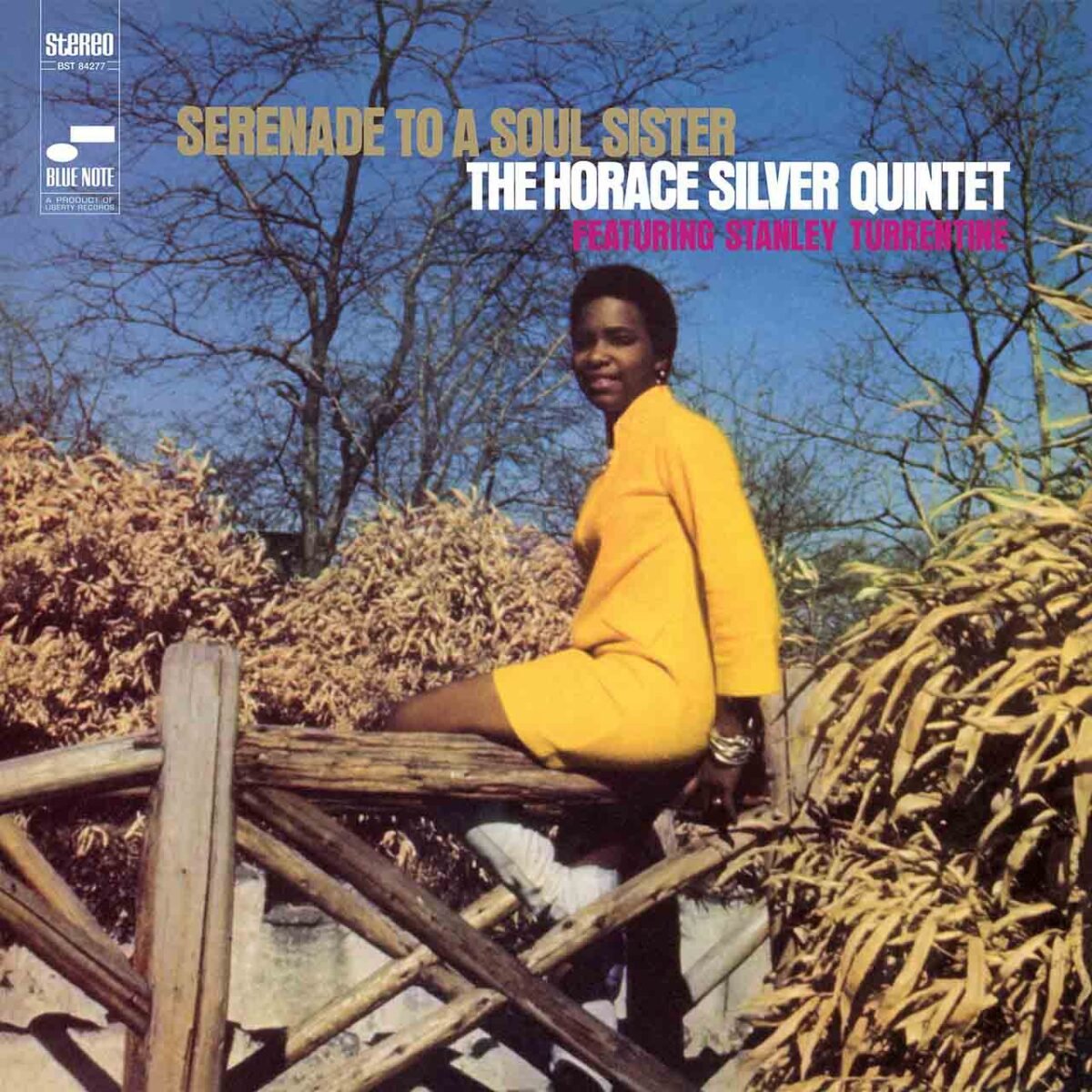

Jacketed in a front cover depicting a “soul sister” photographed by drummer Billy Cobham, Serenade To A Soul Sister’s back cover was devoted to Silver’s extensive liner notes, which even presented unrecorded lyrics to three of the album’s tunes. Their inclusion signposted the pianist’s future recordings with vocals as the late 60s rolled into the 70s. Silver also stated his compositional dos and don’ts, stating that “I personally do not believe in politics, hatred or anger in musical composition,” a veiled critique perhaps of avant-garde jazz’s revolutionary fervor.

Though it could not match the commercial success of Song For My Father, Serenade To A Soul Sister made No. 41 on the US R&B chart. Even so, it’s still an underappreciated gem in Silver’s canon; a soul jazz manifesto whose message still rings true today.

Order Horace Silver’s Serenade to a Soul Sister on vinyl now.