Economic historian Richard Vedder loves teaching so much that he spent his honeymoon—more than half a century ago—in Italy with a group of 43 students. But he believes higher education has strayed from its core purpose of “disseminating and discovering knowledge”—and he has a lot of ideas about how to get it back on track.

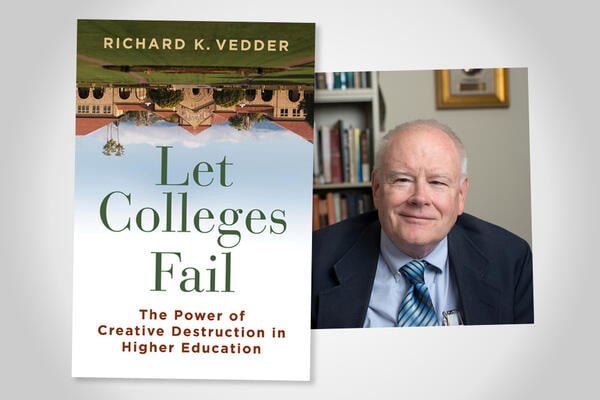

In his new book, Let Colleges Fail: The Power of Creative Destruction in Higher Education (Independent Institute), Vedder, 84, Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Economics at Ohio University and the founding director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity in Washington, D.C., argues that for colleges and universities to regain their public standing, they need to behave more like corporations and regularly reallocate resources from unproductive divisions or programs to those that advance their essential mission.

He spoke with Inside Higher Ed by phone. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: The title of your book, Let Colleges Fail, is pretty arresting. A lot of our readers are actually quite worried about their institutions failing right now. Is it hyperbolic, or do you really want some colleges to fail?

A: It’s a provocative title. But what I say is colleges need to step up their game, or they’re going to fail, and the threat of failing may lead them to become more efficient, better serving the public needs. And if that means that they have to get rid of some administrative staff in doing that, fine. If it means that they may have to use new technologies—or maybe do something radical, like teach kids on Fridays and Saturdays, or go to school nine or 10 months rather than seven months a year? Fine.

The colleges that are literally going out of business are the ones with a marginal reputation. Everyone wants to go to the best place, and as a consequence, the least best places are closing, or are in danger … If you look at higher ed total enrollment today, compared with 2010, it’s down. The U.S. population is growing, admittedly fairly slowly, yet college enrollments are falling. This never happened before in our history, except maybe during a recession or a war. But we’ve never gone more than a decade with college participation declining relative to the population or relative to the economy as a whole.

Q: Your basic thesis is that colleges and universities should be treated more like businesses, right? And they should be expected to show returns for their services or face a takeover, leadership change or, in the worst-case scenario, collapse?

A: The one thing that’s notable about the private sector over the last 100, 200 years of our history is that it has changed enormously. Almost all American corporations at some point or other fail or come close to failing. If you take the Fortune 500 company list for the year 2000, say, and compare it with a Fortune 500 list today, maybe six out of the top 25 are pretty much the same companies, meaning 19 have changed fundamentally. Not all of them have gone out of business, but they’ve undergone significant change—Exxon became ExxonMobil, for example.

I’m really talking about creative destruction. We have to take resources that are used unproductively and make them more productive. Thus companies like Eastman Kodak, for example, or JCPenney, either go out of business or are small shadows of their former selves. And we have other companies—Nvidia, Amazon and so on—who come along and have to raise lots of money from somewhere to finance their enormous expansion. Resources are constantly being reallocated within the sector … I don’t know what the equivalent in higher ed is. We don’t have a good bottom line. We don’t even know what’s a good school and what’s a bad school. But if you take the U.S. News rankings, and you look at their list of top 25, it’s barely changed.

Q: You write that postsecondary education has fallen out of favor with the general public, essentially because colleges are too expensive, too “woke,” not rigorous enough and too detached from the real world. I think even some of the sector’s staunchest defenders would agree with you, yet still not want to see colleges fail. They might say, “Oh, well, we need to do some serious reforms from within.”

A: Yeah, well, that’s really what I mean. Do I want colleges to fail? I mean, I’m not a sadist. I want higher ed to succeed as a general proposition. I think America still has the best system of higher ed in the world … but I want colleges to realize that they need to step up their act and maybe change a little bit more than they have, be more aggressive in reformulating themselves—partly on the cost side, to become less expensive, but also to become focused on job one: teaching and research. It’s the act of disseminating and discovering knowledge, and that’s what we’re about. We do a lot of other things that are distractions—like March Madness. It’s great entertainment, but it’s a ball-throwing contest. If you go to Oxford or Cambridge, you don’t see basketball being played at a professional level, sponsored by the university.

Q: How did costs get so out of hand?

A: The single most important thing, I think, was the growth of student loan programs, which allowed colleges to push tuition fees up … From 1980 to about 2020, the price of college went up much more so than people’s incomes, and so college became less affordable, which added to some public resentment. It used to be you could work and pay your way through college out of just working, but now you can’t do that. You have to borrow a gazillion dollars to pay for it. So that eroded a bit the good will that colleges had, and the feeling that we were out to serve the public interest. And people said that colleges are kind of expensive and they’re selfish, and then there were mass increases in administration. We’re adding more and more assistant deans of this, associate provost for that, chief of staffs. What is a chief of staff? I don’t know.

Q: So do you believe higher education is a public good?

A: It has an aspect of being a public good potentially, but I think that claim is overrated. I think the main benefits of going to college accrue to the individuals who go.

Higher ed, most of stuff they’re doing is good. But there is also maybe a negative externality. Maybe when you declare war on Jewish people, or try to shut down campuses, and you cause damage, that is actually a negative externality. You’re detracting from the good. And so I think the negative externalities have grown over time, so that we have less of a pure public good than we used to. The argument for public support has declined. That doesn’t mean necessarily to zero, but it has declined, and I think it shows up in all this legislation we’re seeing on DEI and all that stuff, not only at the federal level but in the states.

Q: There’s clearly a disparity of opportunity in this country. Don’t you think that the point of DEI was to extend more opportunity to more people?

A: Like nearly everything, there’s good purpose behind it. There’s good purpose behind Pell Grants. There’s good purpose behind student loan programs, but as I say, they got used for not-so-virtuous purposes. We used a lot of the money we raised from student loan programs; we jacked up tuition fees a lot, and then we used this money to hire administrators, pay higher salaries. I could talk to you about university president salaries, for example. In 1995, the president of the University of Michigan made $175,000 a year. In today’s dollars, that’s $400,000 maybe. Today, last I looked, the University of Michigan president was making a million.

Q: The problem is that the colleges that are most likely to fail are either small regional publics, or branch campuses, or small privates that often serve a pretty remote local population, and then what happens to those people?

A: Well, first of all, it isn’t like colleges are going to go completely out of business. If we got rid of 500 of these, let’s call them marginal colleges, it still leaves a couple thousand other colleges, so I don’t see the number falling so far that people would not have access to colleges. I mean, I live in a poor area in Appalachia, so I’m kind of familiar. My wife is a guidance counselor and is having an awful time getting kids to go to college. It’s tough; it really is. So if some of these smaller schools go out of business, some of these kids will go somewhere else; maybe a few of them won’t go—that’s possible.

Q: What about online education?

A: I always thought online had great potential. And I must admit, my own position on this has changed somewhat over time. I was forced into teaching online during the pandemic, and we did what we had to do under the circumstances. But I do think it was a less satisfactory educational experience—a lot less satisfactory. I didn’t realize until after that how important these personal interactions with students are. I spent an awful lot of my career interacting with students outside of the class. After I got married—56 years ago, by the way—we took 43 students with us on our honeymoon.

Q: What? Why?

A: Well, I had agreed to take a group of students to Italy first, then I asked my wife to marry me second. The timing wasn’t exactly optimal, but it really worked out well. My wife was 22 years old, she had just graduated herself from college, so we went to Italy, and she took courses in Italian and so forth, and I was teaching economics.

I took my last group of students, to Prague, four or five years ago, at age 79. I’ve been doing that for years, because I think there is more to life and more to college than just going to class. And I think these interactions and the cultural learning about other cultures is important, and online education doesn’t achieve that.

Q: Instead of letting small colleges in the middle of nowhere fail, what about helping them merge?

A: I think it’s a good approach. As the college population declines, what’s wrong with two schools, 10, 20, 30 miles apart, merging and allowing students to go to either campus or two campuses and maybe ultimately move to a single campus? That’s part of innovation. There’s been a lot of merging, as you know, in Pennsylvania’s PASSHE system. They merged six schools into two, but I thought that was, on the whole, probably a good move.

So when I say let colleges fail, “fail” could mean merge; it doesn’t necessarily mean closing your doors and saying, “Don’t you dare come near this place again. We’re gonna sell these buildings and make them into a warehouse” or something.

Q: How does what the Trump administration is doing—freezing funding, dismantling the Education Department, eliminating accreditors and so on—fit with your thesis?

A: I think a little bit of disruption and chaos sometimes stimulates the creative juices, leads to change—creative destruction—that wouldn’t otherwise happen. But I must say there’s a little more chaos and a little less deliberate reasoning around changes than would be optimal. And it’s happening too fast, and in a disorderly fashion. I think the Department of Education needed to be shaken up a bit. I have jokingly said that I wanted the Air Force or someone to bomb the Maryland Avenue building out of existence and turn it over to the Smithsonian. It’d be a great location for an addition to the Air and Space Museum.

Q: So if you support abolishing the Ed Department, then what do you wish they would do differently?

A: I think, for example, on the student loan program, if you get rid of 80 percent or 60 percent of the people involved with administering the student loan programs, you’re going to have chaos. And the Department of Education has been terribly inept; last year’s FAFSA fiasco is an example. Trump, by letting lots of staff go overnight without sort of planning an orderly retreat, is going to cause some hardship, and some people are going to be … poorly treated by our government. But out of chaos, maybe that’s the only way—maybe this is the thinking of the Trump administration—the only way that you can really take on the higher education establishment. And I do think the higher education establishment needs to be taken on.