As more nations adopt the colour-coded approach, a metaphorical kaleidoscope featuring green, blue, orange, silver, and other shades are now being used to define distinct but interconnected domains of economic activity. For experts, the addition of colours provides a flexible tool to describe economic change and the synergies that lie within.

In a global economy that is becoming increasingly complex, a vibrant framework is helping to bring clarity and visibility to how people understand and analyse economic output from traditional and emerging sectors.

Referred to as ‘coloured economics’, the framework is used to categorise economic activities based on colours. It uses different shades to represent specific objectives and characteristics, often with a focus on sustainability and inclusive development.

Throughout history, different economic models have arisen in response to specific social, environmental, or political challenges. But as countries moved into the 20th century, more creative approaches emerged — ones that not only sought to transform economic structures, but also promote global solidarity and long-term stability.

Much like artists who use colour to add emotion and dimension to their creative works, economists and policymakers are now using shades to better map the modern economy. As a result, the coloured economics framework aims to create a more nuanced understanding of sector-specific challenges and the growing interconnections among industries. While each colour reflects a unique area, together they form one integrated and dynamic economy.

Dr Peter-John Gordon, lecturer in the Department of Economics at The University of the West Indies (The UWI), Mona, commenting on the usefulness of this model, told the Jamaica Observer that while personally he doesn’t interpret the economy in colours, he sees value in the approach.

The use of this model, which may help to visualise how different sectors adapt to technological advancements, environmental concerns and global market shifts, could also influence employment trends, workplace conditions and overall economic growth.

“This colourisation is just another way of segmenting —similar to how we separate the goods-producing and services industries — while still understanding that it’s one economy. It’s about grouping emerging and traditional sectors, such as the blue economy, which previously may have been overlooked but will now gain more recognition through this classification,” he stated.

UWI colleague and culture and creative industry specialist Dr Deborah Hickling Gordon, further touting the use of colour as a form of symbolism, said it serves as a practical means of communication, particularly when used to reference those newer or overlapping sectors.

“I don’t believe the colouring should be seen as a fragmenting of the economy. These sectors are already defined and segmented within the framework. What colourisation, however, does is simply offers a way to analyse them either comparatively or independently based on their economic impact,” she explained.

Hickling Gordon stressed that with overlapping sectors such as tourism, culture, and entertainment often operating synergistically, being able to assess them independently via colour or other frameworks —can help countries to identify their unique growth potential.

“For emerging sectors, colour-coding is especially helpful. It allows us to collect and interpret data in areas we may have previously overlooked. Grouping sectors like the blue and green economies will also allow us to move the needle forward concerning sustainable development,” she added.

As more nations adopt the colour-coded approach, a metaphorical kaleidoscope featuring green, blue, orange, silver, and other shades are now being used to define distinct but interconnected domains of economic activity. For experts, the addition of colours provides a flexible tool to describe economic change and the synergies that lie within.

The green economy, said to be the earliest of the color-based models, focuses on ecology and sustainability. It aims to minimise environmental degradation by promoting renewable energy, green manufacturing, and eco-friendly practices. This concept has over the years evolved from simply mitigating environmental harm to more encompassing goals such as poverty reduction and inclusive growth.

Closely related is the blue economy, centred on marine and freshwater ecosystems. It includes sustainable fisheries, aquaculture, and water-based tourism, with an emphasis on ecological preservation and the livelihoods of coastal communities. Celebrating human creativity, the orange economy, on the other hand, covers arts, entertainment, fashion, architecture, advertising, software, publishing as well as research and development. Often under-recognised in value, this sector sector makes vital contributors to innovation, identity, and economic resilience.

In desert regions where a yellow economy is also emerging, this is used to represent development models that harness arid landscapes through solar energy, sustainable agriculture, and desert tourism. It reflects the ingenuity of adapting economic models to some of the world’s most challenging environments.

As countries and economic experts continue to further weigh output in colours, an evolving scheme infusing red, silver and even black further brightens the spectrum.

The silver economy, in recent times ranking as an important area of focus, is used to assess aging populations, doubling down on age-friendly innovation, senior entrepreneurship, healthcare services, and retirement planning. In keeping with global demographic shifts, it is becoming central to long-term economic planning. Juxtaposed to it is the white economy which spans healthcare and social care services, involving all things concerning the production, research, marketing and distribution of health-related goods and services. Touted as the backbone of societal well-being, important healthcare facilities such as hospitals, pharmaceutical and medical technology fall under this category. This economy is aptly coloured, imitating the white coats of clinicians and the sterile environments of medical institutions.

The gold economy, on the other hand, shining the light on digitalisation and high-tech innovation, largely focuses on advanced technologies and fintech to premium digital services. It underscores the growing dominance of data and connectivity in shaping future economies.

Less popular but also getting some amount of attention are developments in the black economy, which is increasingly being used to represent illicit and underground activities such as drug trafficking, money laundering and terrorism. Its presence often distorting development, increases inequality, and threatens global stability. Similarly, the grey economy, which makes little to no contributions to GDP, largely covers informal economic activities for which enterprises, jobs, and workers are usually not regulated or protected by the State. This economy has, however, helped to establish self-employment in small, unregistered enterprises.

As the various shades continue to pop up, giving structured meaning to output, each colour standing on its own also reflects the real power of the framework which lies in how the sectors interact. For instance, advances in the gold economy can be used to support clean energy in the green economy or digital health-care solutions in the white economy. Similarly, cultural assets from the orange economy can similarly boost eco-tourism linked to the blue or yellow economies.

As global challenges ranging from climate change to population aging and digital disruption — reshape future development, this colour-coded framework not only offers countries a way to respond with both structure and creativity but also gives economists, governments, and industries a shared language for recognising and supporting diverse economic activities.

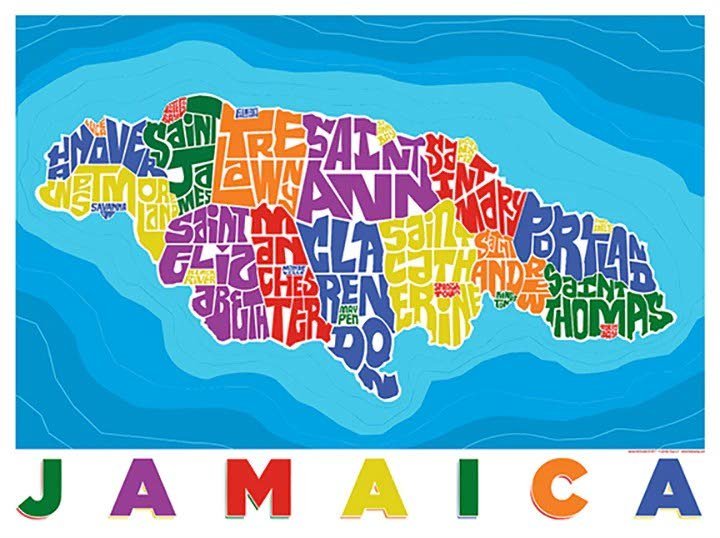

Historically, Jamaica’s economy, which was once grounded in agriculture, has since the post-independence era diversified into other sectors such as mining, construction, tourism, and manufacturing. Today, with increasing focus on sustainability, the country has however started to place greater emphasis on the development of “eco-economies,” particularly in the green and blue areas — sectors seen as key to long-term, resilient growth. According to World Bank data, the local economy is expected to grow by 1.7 per cent in 2025 banking on stronger growth from the popularly coloured segments including the gold economy where artificial intelligence and technological advancements are fast becoming the drivers of modern development.

Gordon cognisant of the fact that we now operate in a world which can no longer be seen in just black or white, said that as societies progress and new sectors emerge, it likely that more colours could be added to highlight new areas of economic activity.

As these colours are added, the economist, however, cautioned against any practice that will prioritise one area at the expense of others.

“We shouldn’t discriminate against any part of the economy because at the end of the day it’s one economy, and as such national focus should be largely placed on how all segments can work together to generate meaningful output,” he said.