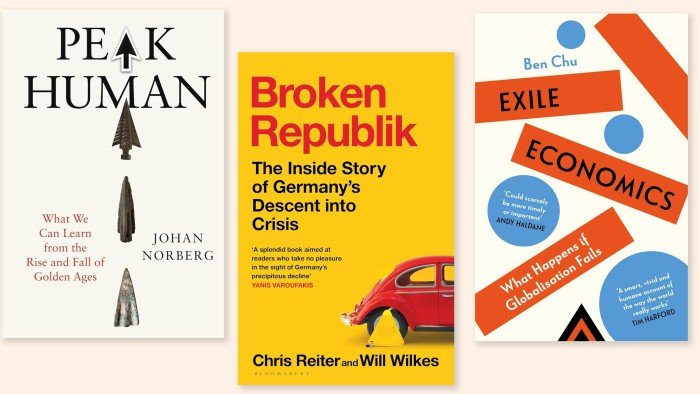

In Peak Human: What We Can Learn from the Rise and Fall of Golden Ages (Atlantic Books £22), Swedish historian Johan Norberg offers a compelling and timely study of what drove history’s most influential civilisations. Through a fascinating examination of seven of the greatest golden ages — from ancient Greece and the Roman Republic to Song China and the Abbasid Caliphate — Norberg finds that cultural flourishing, scientific discoveries and economic growth was powered by two factors: first, a desire to imitate; second, a drive to innovate.

Both were facilitated by a passion for exploration and an openness to trade, foreign peoples and ideas, which enabled civilisations to update their technology and knowledge and subsequently, improve upon them.

Norberg shows how a constant willingness to challenge inwardness and convention led to social and economic development. Of the 17th-century Dutch republic, he notes “[its] openness to refugees and debate made it the epicentre of the European Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment”. Downfalls, by contrast, tended to be the result of a series of crises, such as financial crashes, pandemics and geopolitical tensions, combined with bad governance. This often replaced “the confident, exploratory mindset with a sense that the world is dangerous”, leading to stagnation and ideological rigidity. The overcorrection towards protectionism is the preserve of both the hard, national right and the illiberal left, argues Norberg.

The book comes with impeccable timing. Many are now questioning whether the drive for globalisation during the past few decades, which has seen immense progress in poverty reduction and economic growth, is now reaching its zenith. As ever, Norberg ends on a hopeful note. He believes that recent progress in creating a global civilisation (in terms of knowledge and skills), in part a function of the international digital economy, means that no one country will hold a monopoly on the ideas that support prosperity.

“Every civilization has a bit of the Athenian and of the Spartan within it,” says the historian. “We decide who we let out.” This is an entertaining and informative read for anyone interested in the forces that shape how civilisation’s progress.

Ben Chu’s Exile Economics: What Happens If Globalisation Fails (Basic Books £25) reinforces Norberg’s findings. In what will now be familiar to readers, the policy and analysis correspondent at BBC Verify explains how faith in globalisation has weakened in the aftermath of the pandemic, energy crisis, and trade rivalry between the US and China, leading to the rise of zero-sum economic thinking. Indeed, protectionism — restricting the flow of goods, services, people and investment across international borders — has been rising across the world, not just in Trump’s America.

However, Chu’s more significant contribution to this genre comes from his convincing exposition of why interdependence and multilateralism will prevail in the long-run, which he achieves through an in-depth illustration of the innate economic advantages of global supply chains, from food and energy to high-tech chips. In this way he shows how the desire for self-sufficiency is itself not attainable without at least a bit of interconnection and community.

Germany is a prime example of a country that is facing a backlash against globalisation. In Broken Republik: The Inside Story of Germany’s Descent into Crisis (Bloomsbury £22), Chris Reiter and Will Wilkes detail how the European Union’s largest economy has gone from a case study in successful economic development to a symbol of decline. Rising inequality and industrial decline are part of that story.

Echoing Norberg, the authors point the finger at a social and political system that has made Germany resistant to change — which has, in turn, made it easier to scapegoat the forces of global trade and immigration. Although a new government has been installed since this book was released, the authors nonetheless provides a deeply insightful and fresh view of the challenges Chancellor Friedrich Merz will need to overcome if he is to correct Germany’s trajectory.

Making Money Work: How to Rewrite the Rules of Our Financial System (Wiley $34.95) by Matt Sekerke and Steve Hanke is a must-read for monetary economics afficionados. The authors provide a rigorous explanation of how monetary, banking and capital market systems work, shedding light on some common misconceptions around how money is created and destroyed in our modern economies.

In the process, they outline a few flaws in need of fix, including how regulation and fiscal policy determine and constrain interest rate setters just as much as central bankers’ own actions. More interestingly, Sekerke and Hanke offer an outline of what a better financial system might look like, from banking reforms to transitioning towards a quantity-based monetary policy framework.

Tej Parikh is the FT’s economics leader writer

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X